The first thing we did for this Journey is, obviously, watch Wargames! Happily, it's currently free with ads on YouTube:

I LOVE Wargames as the ultimate computer hacker, retro, semi-apocalyptic vision of what living with all-powerful computers can be and the importance of careful programming.

It also has the ultimate pro tip for how to butter your corn on the cob. Watch for it, and thank me later.

Deep Blue and Watson are real examples of computers learning how to play games, and fortunately, there are also tons of easily available videos covering the process of creating, programming, testing, and troubleshooting the computers. Here are two of the several that we watched:

There's so much more to get into, though, if your kids are interested. You can replay those literal chess games, following the algorithms or going off on your own, or talk about Jeopardy game theory--all of that is not just super interesting, but increases a kid's appreciation of all the variables that go into creating a computer program that can not only mimic game play, but win it!

After all that, what better way to model this process of teaching a computer how to play a game than by playing that Wargames gold standard, Tic-Tac-Toe?

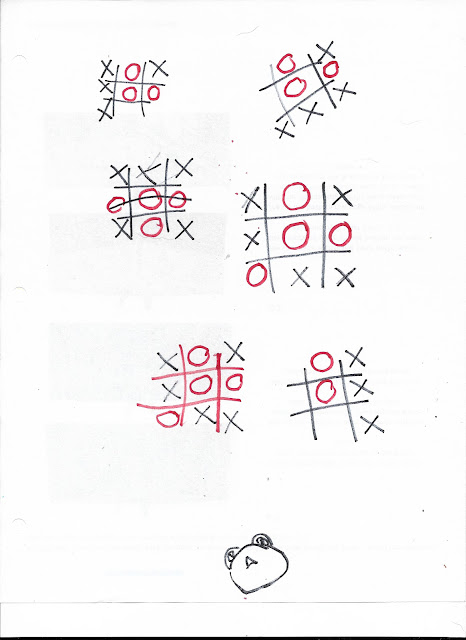

First, the kids and I all played a few (million) games of Tic-Tac-Toe, because Tic-Tac-Toe is never not fun.

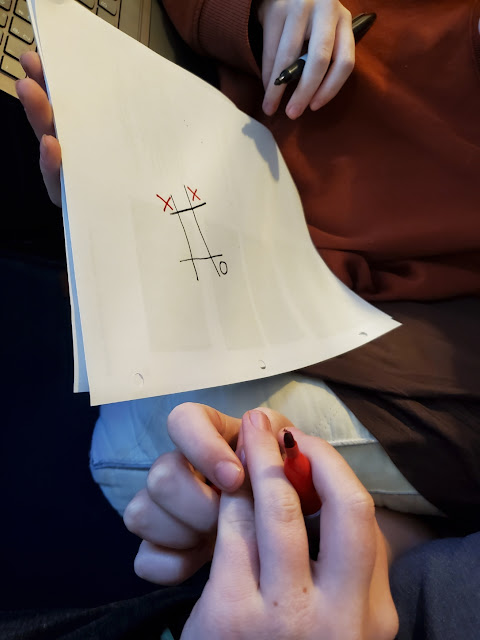

Next, I reviewed the concept of the algorithm, and then modeled playing Tic-Tac-Toe while following a set algorithm... a program, doncha know?

Then, I challenged each of the kids to create an algorithm for winning a game of Tic-Tac-Toe. The rules are to create a step-by-step program that they must follow exactly when playing an opponent, but they may use "OR" and "IF...THEN" commands.

And then... we played!

We tried some various permutations of a computer playing against a person, two computers playing each other, playing X vs. O, etc.:

The ultimate lesson, of course, is the same one that Joshua learned during Wargames--you can't really bank on winning Tic-Tac-Toe. Especially if you're the human playing against the algorithm, you can use your own creativity and spontaneity against the program.

If you want to write a program, then, you need to write it with these caveats in mind: 1) A computer can only do what you've programmed it to do, and 2) humans don't have programming, so they can do literally ANYTHING.

If you want to offer another type of model to help kids develop a more nuanced definition of programming, you can also show them mathematical map coloring. A strategy is just another term for "algorithm," so kids could also develop their strategy for four-color map coloring, then test it, problem-solve it, give it to another kid to beta test, etc.

P.S. If you want to sneak in some high school English credit, have your kid read Ender's Game and write a paper comparing it to Wargames. They both came out at about the same time, with a historical background of the Cold War. They're both about gamifying war by manipulating beings who do not have the lived experience to throw off these manipulations, and they both question how the use of technology affects culpability. Powerful stuff, and issues that it's really good for teenagers to explore.

P.P.S. I'm overly attached to my Craft Knife Facebook page, and I post there way too often. Come find me!

No comments:

Post a Comment